Buffett Loads Up On Treasury Bills -- WSJ

February 24 2018 - 2:02AM

Dow Jones News

By Nicole Friedman and Daniel Kruger

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (February 24, 2018).

Berkshire Hathaway Inc. shareholders will look to Warren

Buffett's annual letter on Saturday for new clues of what the

conglomerate plans to do with more than $100 billion in cash.

There is little mystery about who is getting that money

meanwhile: Uncle Sam.

Berkshire has used its mounting cash pile to become one of the

world's largest owners of U.S. Treasury bills after struggling to

find big companies to buy in recent years.

It held $109 billion in cash as of Sept. 30, up from $86 billion

at the end of 2016 and more than double what it had at the end of

2006. Nearly all of that was invested in short-term bills,

according to Mr. Buffett.

Berkshire has an outsize presence in the $2 trillion market for

Treasury bills, a type of government debt that matures in a year or

less. It held more bills around the end of the third quarter than

large countries such as China and the U.K. It also had more at that

time than the $13.5 billion held collectively by a group of 23

primary bond dealers that are obligated to underwrite U.S.

government debt sales.

Berkshire's holdings are big enough that when bond dealers need

bills for a specific date, they will come to Berkshire and arrange

a trade, Mr. Buffett said.

"We're the ones they call. We've got the best inventory," Mr.

Buffett said in a 2017 interview with The Wall Street Journal.

"That's a new sideline for us here."

Shortages of Treasury bills have been a particular problem for

bond dealers and investors at recent points. When the U.S.

government approached its debt ceiling in recent years, the

government was sometimes forced to sell fewer bills, making them

scarce in the market. A recent budget deal pushed back the next

debt-ceiling showdown until March 2019.

The Omaha, Neb., billionaire uses his widely read annual

shareholder letter to recap Berkshire's results and discuss broader

financial themes. He typically says little about where he could

turn next for an acquisition, although he has acknowledged in other

settings that pressure is mounting for Berkshire to find better

uses for its massive cash holdings.

Those holdings grew by an additional $3.3 billion last week when

Phillips 66 repurchased 35 million of its shares from

Berkshire.

"There's no way I can come back here three years from now and

tell you that we hold $150 billion or so in cash or more, and we

think we're doing something brilliant by doing it," he said at

Berkshire's annual meeting last May. "I would say that history is

on our side, but it would be more fun if the phone would ring."

Berkshire hasn't made a major buy since it agreed to acquire

aerospace manufacturer Precision Castparts Corp. in 2015 for more

than $32 billion, its biggest deal ever. A deal last year to buy

Texas power-transmission company Oncor for $9 billion in cash was

terminated after Oncor's parent company got a higher offer.

Mr. Buffett has long resisted using cash to pay a dividend,

partly because of the tax consequences for shareholders. He has

said the company would buy back stock if its price falls below 120%

of book value. Both classes of Berkshire stock traded Thursday at

165% of book value.

"He's aware that [Berkshire's cash] is not earning a high rate

of return for shareholders," said David Kass, a professor at the

University of Maryland's Robert H. Smith School of Business and a

Berkshire shareholder. "Paying out a special cash dividend, a

one-time dividend at the discretion of management, makes some

sense."

Berkshire earns revenue from holding and trading its Treasury

bills, but the profit is minimal relative to its overall business

operations. Berkshire's head trader, Mark Millard, declined to

comment.

Other corporations with large cash holdings tend to invest in

higher-yielding assets such as corporate bonds. But Berkshire

prefers to hold Treasury bills because they would provide more

liquidity during a market downturn, Mr. Buffett said on CNBC last

month. Mr. Buffett used Berkshire's financial strength during the

financial crisis to throw lifelines to companies including Goldman

Sachs Group Inc. and General Electric Co. in 2008.

"I believe at some point in the future, they'll be rewarded,

[and] we'll be rewarded as shareholders, for having all that cash,"

said Trip Miller, managing partner of Gullane Capital Partners LLC

in Memphis, Tenn. "They'll be sitting there ready to pounce."

Mr. Buffett's current involvement in the Treasury market is less

stressful than one in the early 1990s. Mr. Buffett stepped in as

chairman of Salomon Inc. in 1991 after a rogue trader was caught

trying to corner the market in two-year government debt by

manipulating the auction process to buy more bonds than

allowed.

Berkshire typically buys about $4 billion in Treasury bills

every Monday at government auctions, or less than 4% of what the

Treasury is selling, Mr. Buffett said on CNBC in January. He joked:

"We're very careful about how many we bid for."

Write to Nicole Friedman at nicole.friedman@wsj.com and Daniel

Kruger at Daniel.Kruger@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 24, 2018 02:47 ET (07:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

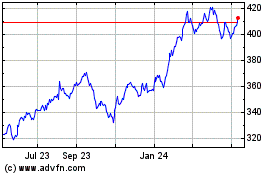

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.B)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

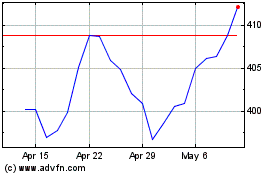

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.B)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024