By Mike Colias

General Motors Co. is betting its future on electric cars. By

mid-decade it plans to spend $27 billion on manufacturing 30

electric models and developing driverless cars. By 2035, it expects

to have phased out gasoline-engine options completely and to be

selling only electric vehicles, a technology that currently

generates about 2% of sales and no profit for the company.

Planning for this transformation at the factory level is the

responsibility of Gerald Johnson, a GM lifer who took over global

manufacturing operations in 2019, and who is spearheading a $2.2

billion gut rehab of a factory in Detroit, recently renamed Factory

Zero, to serve as GM's electric-vehicle hub. Two more conversions

of North American factories for production of electric vehicles, or

EVs, are in the works.

Mr. Johnson, 58 years old, calls it the most far-reaching

strategic shift he has seen in his career at GM, which he began 40

years ago as an intern.

"There has always been incremental change," he says. "This is

transformative."

GM factories around the world employ more than 100,000 workers.

Some plants exist solely to assemble gas-powered engines and

transmissions that won't be needed if the company successfully

reaches its 2035 target, portending big changes for both workers

and GM's factory footprint.

Addressing disruption is nothing new to Mr. Johnson, whose

duties have included managing labor relations through a bitter

40-day strike at GM's U.S. factories in 2019 that drained $3.5

billion in profit. Last spring, his team led GM's effort to make

ventilators after Covid-19 hit the U.S., closing car factories for

nearly two months. Now, continuing supply-chain disruptions are

hampering efforts to make up for lost output.

The Wall Street Journal talked to Mr. Johnson recently. Here are

edited excerpts.

WSJ: Electric cars are breaking down some of the barriers to

entry that have protected big car companies. How can GM maintain

its edge?

MR. JOHNSON: From an engineering standpoint, electric vehicles

of course require a lot of technology and innovation. The holy

grail is finding that cost balance between electric range and the

cost of a battery.

But the integration [of GM's own electric powertrain into its

own car models, in effect producing everything in house] is the

piece that I think is going to enable us to run further and faster.

Integrating this technology into a vehicle platform in such a way

that allows all the functionality that we currently offer, but the

added capability of an EV -- that's where I think GM is going to

show out based on our track record.

WSJ: You're saying even though it has become easier for others

to put together battery systems and offer electric cars, there's

more to it than that?

MR. JOHNSON: Yes. There are the specific elements of figuring

out the technology cost curve, and we're doing that. But I think

where we will leapfrog others is on everything else that goes into

the vehicle. We think we have an advantage with our supply base,

with our ability to integrate our software capabilities. We also

have an established dealer network that can help us.

WSJ: GM is spending more than $2 billion to convert Factory Zero

to make EVs. What has to happen to make that conversion?

MR. JOHNSON: Other than the outside walls, everything in Factory

Zero is new. We're putting in a new body shop because we have to

tool for the new vehicles. There's a new paint shop, which is a

significant portion of the investment. And all-new conveyance

systems and automation. We're also doing things like putting in

solar panels to provide power to the grid. Factory Zero will not

just produce vehicles that are emissions-free; we're going to be

based on renewable energy in the factory as well.

WSJ: It has been a few decades since GM last built a new plant

in the U.S. What advantages come from starting with a clean

sheet?

MR. JOHNSON: First, the plant will build solely EVs, so we get

to optimize it for that. We don't have to carry what we would call

"scar tissue" of having a large engine-buildup area. And, because

the weight of an EV is greater, we'll need a more robust conveyance

system.

WSJ: Electric cars are less complex than gas cars and require

far fewer parts. How does that change the factory and what exactly

workers do?

MR. JOHNSON: Probably the biggest piece will be in an area that

would have been dedicated to engine buildup, when we bring an

engine in from one of our powertrain facilities and add all the

additional components. There's a whole line and area dedicated to

that, along with marrying it up to the transmission and

subsequently to the body of the vehicle.

Well, in the EV world, it's a battery pack. It's our Ultium

platform that rolls in and all marries up to the vehicle and makes

it even easier to integrate versus earlier versions of our EVs.

WSJ: How will workers' skills need to change?

MR. JOHNSON: There are two pieces. One is the ongoing innovation

that happens through automation and other work. Every year, with

every new vehicle program, we upgrade the technology it takes to

process a vehicle. That requires additional skilled trades and a

digital understanding.

The most impressive piece is the data analytics that are now

being embedded in the diagnostics that we use in our equipment.

That allows our operators to have a much richer understanding of

what's going on, what actions we need to take to keep the equipment

running.

WSJ: What about as you transition to making electrics and

eventually autonomous vehicles?

MR. JOHNSON: At a place like Factory Zero, we're going to have

multiple product programs that will take a higher level of

adaptability -- both in the tooling and in the kind of work that

they're going to have to be able to do, with longer cycles and more

variation.

WSJ: So workers on an assembly line may be performing more

complex tasks that take them longer per job than they might

today?

MR. JOHNSON: Exactly. The cycles will require more complexity of

execution per station and per operation. Versatility and

adaptability will be important because work flows will be different

in this environment.

WSJ: Given that EVs require less manpower, should workers be

worried about there being fewer auto factory jobs in that

future?

MR. JOHNSON: I think every GM employee should be excited about

what we're doing. Because we see our EV strategy in total as a

full-on growth strategy. We will expand. Yes, some job assignments

will change, but we will have opportunities for everyone to come

along with us as we make this transformation. There will be more

work available in that future than what we have today.

WSJ: The company sees electric vehicles as a growth play, rather

than simply replacing its gas-powered business?

MR. JOHNSON: This is all about growth for us. One reason is that

it allows us an opportunity in the markets where EVs are popular

and where we have the greatest opportunity to gain market share,

like on the West Coast, the East Coast and some portions of the

South.

WSJ: What have your discussions been like with the United Auto

Workers about the future workforce and how it's changing in this

transition?

MR. JOHNSON: Work at Factory Zero is going to start to produce

vehicles this year. We are always in conversation with our union

partners about what it's going to take and how we're going to work

together to bring this investment to life. We're going to allow

ourselves enough time to communicate effectively and plan for this

2035 future that we just committed to.

WSJ: GM is bullish on EVs. But what if the sales volumes fall

short? How do you manage that if you've set aside all this factory

capacity?

MR. JOHNSON: We've got a 15-year horizon. We think we've left

enough adaptability in our footprint to be able to meter that

transformation, where there's a good overlay between

internal-combustion vehicles and EVs. How it plays out between 2024

and 2030, for example, we've left ourselves some flexibility based

on market demand. We're confident in that end point. We're just not

sure how the mix will evolve to get to that.

WSJ: You led GM's effort to pivot to ventilator production last

spring when the plants shut down from the pandemic. What did you

learn about the organization from that?

MR. JOHNSON: We've coined the phrase "ventilator speed." That

means pulling together a team and breaking through barriers to get

something done. We see it now with the accelerated pace of

executing our EV strategy. Many of the programs that we've

announced of late, we've already pulled those dates ahead. That's

ventilator speed -- integrating the team in one location so they

can solve problems, and making sure all the resources are there, to

help them not to follow the process, but to follow the speed and

pace to deliver the outcome.

WSJ: Since you've come into this role, you have handled a

strike, the Covid shutdown and restart, and supply-chain disruption

that has affected production. What have you learned about leading

during times of upheaval?

MR. JOHNSON: What I've learned is that our teams are able to

handle it when you support them and focus them on the challenge of

the moment.

We launched a new SUV in Arlington, Texas, in the midst of the

pandemic hitting at the same time. We have accelerated our EV

programs.

My first plant-manager assignment, I pulled up to the plant, and

there were firetrucks all blocking the driveway. My first day and

the plant is burning, smoke billowing through it.

You learn how to problem-solve in the midst of crisis, and

communicate and protect people and focus on what must be done so

everyone can return safely. It's just manufacturing, it's just what

we do.

Mr. Colias is a reporter in The Wall Street Journal's Detroit

bureau. He can be reached at mike.colias@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 20, 2021 11:14 ET (16:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

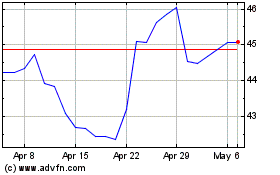

General Motors (NYSE:GM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

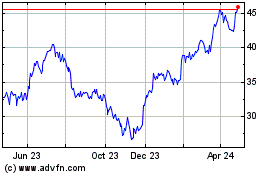

General Motors (NYSE:GM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024