By Mike Colias

Nearly a decade ago, Toyota Motor Corp. dethroned General Motors

Co. as the world's largest car company, leaving some GM executives

wringing their hands.

Mary Barra wasn't among them. When she took the CEO job in early

2014, she inherited a company that for decades was so large and

unwieldy executives sometimes didn't know whether parts of the

business were making or losing money.

On a visit to GM's unprofitable operations in Thailand that

year, she signaled a readiness to curb the company's fixation on

size. She criticized her Asian executive team's five year-plan to

introduce several new models, according to people who attended. GM

soon announced plans to cut Thailand's model lineup, rather than

add to it.

For years, the mantra in the capital-intensive car business has

been that bigger is better. But in nearly seven years running GM,

Ms. Barra has found success with an unlikely strategy: shrinking a

company that for much of the 20th century was the nation's biggest

corporation by revenue and profit.

Now, Ms. Barra is adamant that GM can still grow but in a

different way than in the past: through new businesses built on

electric and driverless cars. Those technologies cost billions a

year to develop, and are likely a long way from paying off. GM

could no longer afford to stay in markets where it doesn't make

money, Ms. Barra, 58, said in an interview.

"We've had to make some tough decisions and move away from

trying to be everything to everyone, everywhere," she said.

Under Ms. Barra, GM has exited Europe, Russia and India, places

where most rivals compete. In February, the company disclosed plans

to leave Thailand for good and pull out of Australia after 89

years.

GM now makes cars or parts in just nine countries, down from 25

before Ms. Barra took over, and employs 164,000 workers today, 25%

fewer than before. Her get-smaller approach is especially unusual

because it came at a time of prosperity in the car business.

Global industrywide auto sales have risen 9% since the year Mr.

Barra became CEO. GM's sales fell 25%.

GM last year was the world's third-largest auto maker by sales,

behind Volkswagen AG and Toyota, and likely would fall to No. 4

after the pending merger between Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV and

PSA Group.

The moves have, until recently, helped GM notch record operating

income and profit margins. And the tidier global footprint aided

the company through the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic,

helping contain the fallout from global factory shutdowns as rival

Ford Motor Co. struggled to contain overseas losses.

The pandemic has only redoubled Ms. Barra's conviction that GM's

future rests on electric and driverless technology. GM preserved

investment in those areas even as it scrambled to cut costs

elsewhere to weather the crisis.

So far, though, investors have largely ignored GM as they pour

money into pure-play electric-vehicle makers.

Tesla Inc. shares have soared this year to make it the world's

most valuable car company. Startups are snapping up billions of

dollars in private investment or recently-launched IPOs, including

truck makers Rivian Automotive and Nikola Corp.

Shares of GM and Nikola surged last week following a deal for GM

to engineer and build trucks for the startup. Nikola shares have

since fallen sharply after a short seller's allegations that it

exaggerated the progress of its technology, drawing investigations

by U.S. securities regulators and the Justice Department.

Nikola has denied the claims. Ms. Barra has said GM did its due

diligence.

GM shares remain stuck below the $33 IPO price from a decade

ago.

Ms. Barra's retrenchment strategy has been anathema for some

inside GM, a company long hard-wired to pursue international

growth. Some former GM executives question whether Ms. Barra is

leaving GM too dependent on the U.S. and China and unable to

capitalize on the moment if India or other developing markets take

off.

For decades at GM, executive stints in overseas markets like

Brazil and China were highly sought after and considered unofficial

prerequisites for the C-suite, said Bob Lutz, a former GM vice

chairman who ran product development from 2001 to 2009.

There also was pride in retaining the world's biggest auto maker

title, he said. Mr. Lutz recalls a TV interview from around 2005,

when he was asked about the possibility of Toyota surpassing GM. He

expressed indifference. Later that day, then-CEO Rick Wagoner

called Mr. Lutz into his office.

"He said, 'Bob, we've got to get our messages together. I happen

to believe there is unbelievable value in being the world's

biggest,' " Mr. Lutz recalls. Mr. Wagoner declined to comment.

The super-size argument goes like this: The bigger a car

company's sales globally, the greater its cost advantages, with the

ability to command better terms from suppliers, whether on engine

parts or ad campaigns.

For GM, expanding into untapped markets overseas was a shortcut

to revenue growth. But markets such as China have become fiercely

competitive, pressuring profit margins. Others places, like Russia

and Brazil, haven't fulfilled their potential because of political

or economic upheaval. It was also hard to reduce costs by selling

the same basic models globally: Regional tastes were too varied and

environmental regulations were rarely aligned.

GM's push to expand dates back to the late 1920s when, under the

direction of longtime CEO Alfred Sloan, it overtook Ford in U.S.

sales and eventually expanded to Europe and Australia.

Mr. Sloan's aggressive growth strategy spawned more than a dozen

brands, hundreds of models and factories in dozens of countries. By

the 1940s, almost one of every two cars sold in the U.S. was made

by GM.

Soon, GM had grown so dominant that it gained a reputation as a

collection of warring fiefs. The heads of its various divisions

operated like CEOs unto themselves, and squabbled over capital

spending and marketing dollars, say former executives and

historians.

Even after its government-led bankruptcy in 2009, GM remained

neck-and-neck with Toyota for the title of world's largest car

company by vehicle sales -- still so big and fractured that

executives in Detroit didn't have a clear view of the profitability

of individual countries, said Dan Akerson, GM's CEO from late 2010

to early 2014.

"Before, as long as the guy in Brazil or Europe was talking a

good game, we sort of left him alone," said Mr. Akerson.

Mr. Akerson appointed Ms. Barra to lead GM's huge

product-development operation. She had begun her career as an

18-year-old intern inspecting fender panels at a Pontiac factory in

suburban Detroit and spent much of her career in engineering roles

inside GM's factories.

Still, Mr. Akerson saw the GM lifer as a change agent impatient

with GM's bureaucracy. As GM's human-resources chief, she condensed

a 10-page dress code down to two words: "Dress appropriately."

In 2011, in her first week as product chief, she had all the

card-key security doors between her office and the engineering

staff removed, viewing them as symbolic of how GM tended to work in

silos.

After becoming CEO, Ms. Barra visited India in 2015 with Dan

Ammann, then GM's president, and Tim Solso, then the company's

independent chairman and now its lead independent director. The

executives were blindsided when they arrived to find a factory

expansion already under way without their knowledge, Mr. Solso

said.

"Mary and Dan were dismayed. They had no idea that was going

on," he said in an interview. "It was a telling example of the old

GM saying 'We have to be the biggest and market share drives what

we do.'"

GM largely exited India about two years later.

Around that same time, a confluence of forces was beginning to

disrupt the car business. Alphabet Inc.'s Google in 2015 tested a

self-driving car on public roads. Apple Inc. was rumored to be

developing a car. Ride-hailing services like Uber were becoming

mainstream.

Ms. Barra, who got her M.B.A. at Stanford University, that year

arranged a week-long trip to Silicon Valley with her top

executives. They chatted with Apple CEO Tim Cook and his team about

industry disruption for a few hours, the people said. They

discussed autonomous-driving technology with Google brass.

Once back in Detroit, Ms. Barra scheduled workshops to sketch

out a growth strategy for GM, based on an evolving view that the

future would hinge on offering alternative ways for people to get

around, such as electric and self-driving cars, said John

Quattrone, Ms. Barra's human-resources chief before his retirement

in 2017.

That would also mean deeper cuts overseas to fund the future,

Mr. Quattrone said. Ms. Barra presented the new vision to nearly

300 executives at GM's proving grounds in suburban Detroit, an

expanse of green meadows and ribbons of asphalt where camouflaged

future models buzz around test tracks.

"We all have to sign up for this plan. If you don't believe in

it, then see John and we'll find a landing spot for you," Ms. Barra

said, according to Mr. Quattrone.

Later that year, Ms. Barra and Mr. Ammann began discussions with

French car maker PSA Group to unload GM's European business, which

had racked up roughly $20 billion in losses in the previous two

decades.

As talks advanced, the two executives made a one-day, round-trip

visit to GM's corporate offices in Germany to break the news that

GM was selling its European business to a stunned Karl-Thomas

Neumann, the division chief who had been trying to engineer a

turnaround, people with knowledge of the visit said.

"When you think about the resources that would have been needed

to have a full lineup there, with no clear profitability in sight,

we had to be real about that," said GM President Mark Reuss, among

Ms. Barra's most trusted lieutenants.

Eventually, the retreats from international markets resulted in

a hangover effect, former executives say. Some costs attached to

those severed business units remained even after the divestitures

-- a Detroit-based engineer or designer who worked on cars for

developing markets, for example.

Late in the summer of 2018, a few hundred of GM's top executives

gathered at a historic brick building in Flint, Mich., GM's first

factory. Ms. Barra dispatched her then-finance chief, Dhivya

Suryadevara, to warn that cost cuts would be needed, people who

attended the meeting say.

On Thanksgiving weekend that year, GM announced plans to let go

more than 8,000 white-collar workers, the cuts hitting the

engineering ranks hard. The company also outlined plans to close

several North American factories and let go thousands more factory

workers, which drew sharp criticism from President Trump.

Ms. Barra in the interview said the changes were strategic and

allowed GM to meld its electric-vehicle team with the broader

engineering enterprise.

Both pieces of Ms. Barra's two-pronged strategy -- exiting

low-growth businesses while plowing the capital into an electric

future -- were on full display early this year.

In February, GM said it would end its Australian Holden brand, a

once-dominant brand and staple of the country's car-crazy culture,

known for rugged pickup trucks and muscular sedans.

In Australia, car enthusiasts and politicians vented a sense of

betrayal.

"General Motors may think the rich history of the Holden brand

in Australia is worthless, but I think it's priceless," said one

lawmaker, Queensland Sen. James McGrath, according to Australia's

Courier-Mail newspaper.

Then, in early March, GM invited hundreds of dealers, analysts

and journalists to its suburban Detroit engineering center. Ms.

Barra made her biggest statement yet that GM was betting its future

on electric cars.

The CEO strolled the floor as visitors ogled a dozen future

all-electric models, some several years from seeing the inside of

showrooms -- a rarity in an industry where future products are

cloaked in secrecy. The models ranged from brawny pickup trucks to

a Cadillac that one executive said would be priced above

$200,000.

GM said it would spend $20 billion developing electric and

driverless cars through mid-decade. It is targeting sales of 1

million electric-car sales annually by then. In Ohio, near a

factory it closed last year, construction began recently with

partner LG Chem on a battery-cell plant bigger than 40 football

fields.

Still, it will be many years before electric vehicles take off,

analysts say. High battery costs are likely to keep prices higher

than conventionally powered cars through most of this decade, and a

dearth of charging stations in the U.S. will dampen consumer

interest, they say.

So far, the early offerings from incumbent car companies have

failed to achieve anywhere close to Tesla's success.

As Ms. Barra showed off GM's future battery-powered cars, she

was also confronting a new threat: a rapidly-spreading global

pandemic. GM spent the spring scrambling to borrow more than $20

billion amid a multiweek factory shutdown from Covid-19, during

which it bled billions in cash.

In June, Ms. Barra sat with top executives inside GM's design

dome, a circa-1950s auditorium where generations of leaders have

reviewed big Cadillac sedans with gaudy tail fins and Corvette

sports cars.

This meeting was different: Ms. Barra and her team sat at a

large table, wearing masks, to decide which future vehicles were on

the chopping block. Details of each model, from minor face-lifts to

major new entries, were spread across large digital wall charts,

including launch dates and sales targets.

Some were delayed, others scrapped altogether. By the end of the

meeting, all of the electric-vehicle projects on the board emerged

untouched, along with a nearly $3 billion renovation of a Detroit

factory and nearby facility to build them, Ms. Barra said.

"The situation allowed us to look at things with a very clear

eye," she said.

Write to Mike Colias at Mike.Colias@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 18, 2020 10:25 ET (14:25 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

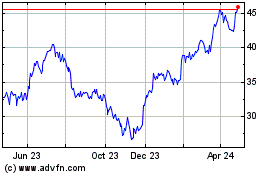

General Motors (NYSE:GM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

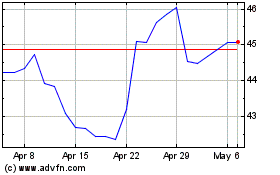

General Motors (NYSE:GM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024