By Sarah McFarlane

LONDON -- Royal Dutch Shell PLC bet big on natural gas as the

energy source of the future when it bought BG Group for $54

billion. Five years later, it appears the gas era won't last

long.

Falling prices for wind and solar power, coupled with government

and businesses' new green goals, are accelerating a shift to

cleaner energy and leaving natural gas -- long seen by energy

companies as a bridge between fossil fuels and renewables -- in the

lurch. The fuel is also under growing scrutiny for methane leaks,

leading some potential customers to skip gas and move ahead to

lower-carbon alternatives.

That is a risk for Shell and rivals such as Exxon Mobil Corp.

and Total SE, which also invested in gas, given that gas projects

typically cost billions of dollars up front and take decades to

recoup that investment.

Shell last month halved its outlook for global gas demand growth

to 1% a year, and said demand for the fuel could peak as soon as

the 2030s.

While burning gas emits less greenhouse gas than coal does,

environmental gains are lost if there is a leakage of methane, the

main component of natural gas. Methane is more potent than carbon

dioxide in contributing to climate change and has become a target

of environmentalists.

"If you look at the global gas industry, its role in the energy

transition and in the world energy mix decades from now is up for

grabs, " Maarten Wetselaar, who heads Shell's gas business, said at

a conference last month, adding that more action to reduce methane

leakage was needed.

Shell is using infrared cameras, lasers and satellites to detect

methane leaks at production sites, during transportation and at

power stations. It has also pushed for policies to reduce methane

emissions from the oil-and-gas industry in the U.S. and Europe.

Shell targets methane-emissions intensity below 0.2% on all its

assets by 2025. Many energy companies don't have targets.

The company has also started selling carbon-neutral cargoes of

liquefied-natural gas, in which emissions can be offset with carbon

credits, and is spending millions of dollars on projects to capture

and store carbon.

Shell said natural gas emits about half as many greenhouse gases

and less than one-tenth of the air pollutants as coal does when it

is used to generate electricity. The company added that it can

still grow its gas business, with demand particularly strong in

Asia, and that it will increase the fuel's share of its production

to 55% in the next decade, from roughly equal with oil today.

However, Shell has already written down the value of some of its

gas assets, including its Queensland Curtis project in Australia.

The project, which it acquired in the BG deal, started in 2015 and

has an expected lifespan of at least 20 years.

Fossil fuels are at risk in the energy transition and natural

gas could theoretically be made redundant by technological

developments, but for now it is still needed, said Irene Himona, an

analyst at Société Générale. What matters to Shell, given its gas

reserves, is what happens over the next 15 to 20 years, she

added.

Moves to curb gas are gaining traction across the West. Several

U.S. cities have banned gas in new buildings, while Ireland is

considering prohibiting the construction of liquefied-natural gas

import terminals. France last year blocked a deal to import gas

from a U.S. seller, citing environmental concerns.

Big corporate buyers, meanwhile, are seeking to reduce carbon

emissions and asking for green, not gas, power. For example,

Amazon.com Inc. has pledged to power its operations with 100%

renewable energy by 2025.

Some industries that Shell and others have targeted to switch to

natural gas from oil-based fuels are now also looking to move

directly to lower-carbon alternatives.

Shipping giant A.P. Moller-Maersk A/S explored liquefied-natural

gas as a fuel option but was put off by methane concerns. Instead

the company plans to launch the world's first container ship

running on biofuel in two years.

"[Liquefied-natural gas] is a fossil fuel and it emits CO2 into

the atmosphere and that's the problem we're trying to solve, so

picking another fossil fuel as a starting point, we don't like that

idea," said Morten Bo Christiansen, Maersk's head of

decarbonization.

Maersk estimates that natural gas reduces carbon emissions from

a ship's chimney by around 25%, but those reductions can be offset

by methane leakages in the supply chain or on the vessel.

"The analysis that we have seen on this are actually suggesting

that even at best this solution is as bad as the problem," said Mr.

Christiansen.

One of Europe's largest trucking companies by fleet size,

Girteka Logistics UAB, has decided against expanding its small

number of liquefied-natural gas trucks partly because of concerns

over methane, focusing on vegetable oil instead. The decision

followed Daimler AG's move to stop developing natural-gas-powered

trucks in 2019.

The pressure on natural gas was apparent earlier this year when

U.S. special envoy for climate John Kerry appeared at odds with

Shell Chief Executive Ben van Beurden over the future role of the

fuel during a virtual Davos panel.

Mr. van Beurden defended the role of gas in the transition to

lower-carbon energy, but Mr. Kerry said he favored minimizing its

use.

"The problem with gas is if we build out a huge infrastructure

for gas and continue to use it as a bridge fuel when we haven't

really exhausted the other possibilities, we're going to be stuck

with stranded assets," Mr. Kerry said, referring to the risk that

20-year gas projects might not be needed.

Write to Sarah McFarlane at sarah.mcfarlane@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 27, 2021 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2021 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

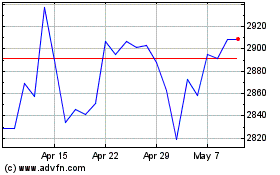

Shell (LSE:SHEL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

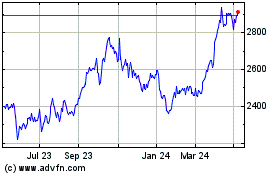

Shell (LSE:SHEL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024