By Rhiannon Hoyle in Jakarta, Indonesia, and Alexandra Wexler in Kalumbila, Zambia

From Congolese jungles to Indonesian highlands, a struggle is

raging between governments and major mining companies over control

of commodities vital to the production of everything from steel to

electric cars to smartphones.

Developing-world leaders, spurred by rising mineral prices, are

making their toughest demands on Western mining companies in years,

squeezing them to pay higher royalties and taxes, process

commodities locally and cede control of mines.

In Indonesia, Rio Tinto PLC and Freeport-McMoRan Inc. were

pressed to sell majority control of the world's second-largest

copper mine, Grasberg, to a government that aims to transform its

state-owned resources companies into industry behemoths.

Tanzania last year slapped a subsidiary of Canada's Barrick Gold

Corp. with a $190 billion tax bill -- four times the country's

gross domestic product. In March, Zambia handed Canada's First

Quantum Minerals Ltd. a tab for import duties and penalties

totaling roughly $8 billion. The Democratic Republic of Congo

signed into law a new mining code in June that will take a bigger

slice of miners' profits. Papua New Guinea, Mali, Sierra Leone and

others have also put mining contracts and legislation under

review.

"I will not hesitate to close down all the mines if companies

don't pay what they owe us," Tanzanian President John Magufuli told

a cheering crowd last year. "I have launched an economic war."

Governments say the countries deserve more of the profits from

the extraction of their resources. Demands for bigger stakes in

resource wealth have risen before -- often when prices go up -- but

people in the industry say fiscal and political pressures now are

hardening governments' resolve to extract more wealth from mining

conglomerates.

A wave of new, populist governments are struggling to pay the

bills after their countries borrowed heavily for infrastructure in

recent years. Governments see miners -- often the biggest companies

in the country, who have little flexibility to leave after years of

investments -- as potential sources of revenue. Prices of many

commodities have recovered, even though they aren't close to record

levels seen roughly eight years ago, and profits of the world's top

40 miners more than doubled last year.

"We are very profitable and therefore everybody -- communities,

governments -- wants to have a bigger share of the cake," Rio Tinto

Chief Executive Jean-Sébastien Jacques said in an interview.

Miners argue they deserve large profits because of the financial

risks they take and the huge upfront costs needed to explore and

build a mine. Still, miners say they have a new understanding of

the importance of disclosure in contracts, and of the need to be

more collaborative with governments to gain what they call a social

license to operate -- the widespread support of the community.

Some mining giants are staying put, contesting the moves or

trying to renegotiate terms with governments, which typically give

them the rights to dig up resources in exchange for royalty

payments. Others are turning to new investments at home, hoping

technology can help revive older sites. Anglo-Australian BHP Group

Ltd., the world's biggest mining company by value, says it wants to

focus on more-predictable places including Australia and the U.S.

after pulling out of South Africa, Mozambique, Indonesia and

elsewhere.

Some miners walking away are selling assets to local investors

or to Chinese companies, who are driven by demand at home and who

don't face the shareholder pressures over risk that Western miners

do. State-owned companies also tend to report less than listed,

international miners.

Mining executives say the resurgence of what they call resource

nationalism could stifle investment in new projects because of

increased costs and risk. Local miners may lack the capital or

skills to operate alone, potentially reducing output, they say.

Countries that depend on resources revenue to fund their budgets

could suffer.

For markets, fewer new supplies could send metals prices soaring

if global growth remains strong, potentially making products from

Tesla Inc.'s Model 3 to Apple Inc.'s iPhones more costly.

In Tanzania, populist Mr. Magufuli took power in 2015 in an

election marked by fraud allegations, and began centralizing power.

After campaigning on a promise to carve out a bigger stake in

resources for the state, the leader nicknamed "the Bulldozer"

canceled mining licenses for many companies, raised royalty

payments and accused Barrick Gold's subsidiary, Acacia Mining PLC,

of underreporting gold and copper production, leading to its $190

billion bill for unpaid taxes, penalties and interest.

The country also seized a U.K. miner's roughly $15 million

shipment of diamonds from an airport, claiming it had been

undervaluing exports, and banned exports of some metal concentrates

to force the development of its local refining industry.

Mr. Magufuli said the moves, which polls show are popular

locally, reset the balance between foreign companies and taxpayers

after many miners received sweetheart deals under previous

administrations.

Acacia, which accounts for 15% of Tanzania's total exports,

denied wrongdoing. Barrick last year said Acacia would pay $300

million as part of a deal to resolve the dispute, or nearly 40% of

Acacia's 2017 revenue, but a final agreement hasn't been

reached.

Acacia's production has nose-dived in the face of Tanzania's

export ban on metal concentrates, and the company has said it is

looking to sell a stake in some or all of its assets in the

country.

Zambia was long seen as being among the most investment friendly

countries in the region, but that has shifted. Its position as

Africa's No. 2 copper producer behind Congo helped spur economic

growth, bringing shopping malls and tidy brick homes to the

landlocked nation.

Copper prices, while healthy, are still down about 40% from

their 2011 peak, leaving the government with deteriorating

finances. Mining accounted for 12% of the country's GDP in 2016.

Zambian government debt is expected to balloon to 66% of GDP in

2018, from 27% five years ago.

First Quantum's Sentinel copper mine, which it built for $2.3

billion, went into production in November 2016. More than 45 giant

trucks haul rock out of the pit daily. Off-duty workers and their

families stroll along paved, tree-lined streets dotted with giant

anthills in a town First Quantum built for over $85 million.

This spring, Zambia delivered First Quantum a nearly $8 billion

bill for what it said were mislabeled import duties on machinery

and materials brought in to build Sentinel, as well as penalties

and interest. "We shall pursue all available options to the

authority to recover all taxes on behalf of the Zambian people," a

spokesman for the Zambia Revenue Authority said in March. Officials

declined to comment further.

First Quantum has denied wrongdoing. "We're just stunned there,"

Philip Pascall, chief executive of First Quantum, said on a call

after the fine was announced. "We completely refute the entire

amount." First Quantum said it was engaging in dialogue with the

government on the issue.

Zambia announced new mine tax measures in September, including a

royalty increase of 1.5 percentage points, a fresh 5% charge on

copper and cobalt concentrate imports and a 15% duty on the export

of precious metals and gemstones. The finance minister said the

measures are intended to ensure that "Zambians benefit from the

mineral wealth."

Across the Indian Ocean, in Indonesia, many foreign miners have

sold operations after years of revisions to mining policies.

Leaders in the mineral-rich archipelago nation have long wanted

foreign miners to share more profits, fueled by concerns they got

cushy deals under former dictator Suharto, who ruled until

1998.

Indonesia has focused on the Grasberg copper mine, by far its

most important asset, and to many Indonesians the biggest symbol of

foreign corporate power.

Located at more than 14,000 feet in the mountains in the remote

province of Papua, it has been a cash cow for Freeport, catapulting

the Phoenix-based company into the ranks of the biggest copper

producers, with $1.8 billion in profits last year.

It has also been a source of local controversy since its initial

contract was signed in 1967, which originally gave no stake to the

government. Contract negotiations then and in the decades that

followed were surrounded by reports of insufficient expertise

within the regime, and insider dealing between Suharto and his

inner circle and Freeport officials, documented in a Wall Street

Journal investigation in the 1990s. Freeport said that its contract

was fair.

The mine was also dogged with allegations that Freeport caused

environmental damage and colluded with Indonesia's military, which

has violently cracked down on separatists who oppose the mine.

Freeport said it adheres to the highest human rights standards and

is committed to minimizing its impact on the environment. It said

it has invested more than $14 billion at Grasberg over five decades

and has been one of Indonesia's largest taxpayers.

With its license running out in 2021, negotiations intensified

last year to give Indonesia more control and profit. Jakarta

canceled Freeport's export permit. "After 50 years we also have to

consider the people of Indonesia," Luhut Pandjaitan, coordinating

minister for maritime affairs, which oversees minerals, said last

year.

Freeport declared force majeure at the mine, laid off more than

10% of its 32,000 workers and threatened to take Indonesia to

arbitration.

Jakarta then threatened to cut off services needed to export

commodities, such as access to customs documentation, to mining

companies that weren't up-to-date with taxes owed under new

permits.

In early 2018, environmental officials ordered Freeport to start

recovering 95% of its waste from a nearby river in which it

discards the material known as tailings, from 50% of the waste

now.

Freeport chief executive Richard Adkerson said that was

impossible. "It cannot be done within six months, 24 months, five

years...This is so far out of bounds," he told investors. He said

he feared political motivations were behind the move.

Jakarta said the move wasn't politically motivated and was

sparked by violations seen during a site visit. Freeport's share

price fell 15% on the day the news became public. Shares are

currently near an 18-month low.

A deal was signed in September in which state-owned PT Indonesia

Asahan Aluminium, or Inalum, will pay $3.5 billion to Rio Tinto for

its interest in Grasberg and $350 million to Freeport, pushing

Inalum's stake from 9.4% to 51%. Freeport will retain 49% and

operate the mine. Mr. Adkerson earlier described the result as a

"major concession" but necessary for continued investment

there.

Freeport is hiring for a new copper project in Arizona, joining

the ranks of Western companies who are working to expand operations

in the U.S., Canada and Australia. The Lone Star resource was found

during exploration near the company's Safford mine, and production

is expected to begin by late 2020. Freeport forecasts the mine will

produce about 200 million pounds of copper a year, with a life of

around two decades.

Rio Tinto and BHP say autonomous vehicles and the ability to dig

deeper because of advanced climate-control systems and data

analytics have made it economically feasible to mine areas far

underground, such as at the pair's joint-venture Resolution Copper

project in Superior, Ariz.

South32 Ltd., a BHP spinoff, recently bought Arizona Mining and

its Hermosa zinc, lead and silver project in Santa Cruz County,

Ariz., for $1.3 billion. The company is working to unload a coal

unit in South Africa, where government policy requires miners to

sell large stakes to black-owned entities.

"We want to go to places where we are welcome and the friction

towards our investment is low," BHP chief executive Andrew

Mackenzie said in May.

--Nicholas Bariyo in Kampala, Uganda, contributed to this

article.

Write to Rhiannon Hoyle at rhiannon.hoyle@wsj.com and Alexandra

Wexler at alexandra.wexler@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 18, 2018 14:32 ET (19:32 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

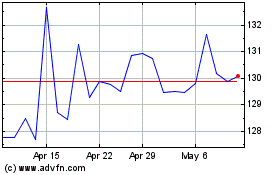

Rio Tinto (ASX:RIO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Oct 2024 to Nov 2024

Rio Tinto (ASX:RIO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Nov 2023 to Nov 2024