By Tom Fairless

SOLINGEN, Germany -- Zwilling JA Henckels, a 300-year-old

knife-making company based in this ancient city of swordsmiths, had

much in common with Italy's Bialetti Industrie SpA.

Both are family-owned companies that produce signature cooking

tools -- knives for Zwilling and, for Bialetti, a whistling

stovetop coffeepot. Both diversified into a range of cooking

products in recent decades and entered international markets with a

network of stores.

Then the euro came along 20 years ago, binding Germany and Italy

more tightly into Europe's giant single market. And the fortunes of

the two companies started to diverge.

Over the past decade, Zwilling has more than tripled revenue to

EUR700 million (about $800 million) -- while Bialetti's sales have

fallen 20%, from a similar starting point of around EUR200 million.

In October, Bialetti said it had agreed to a debt-restructuring

deal that will hand an equity stake to Och-Ziff Capital Management,

the New York-based hedge fund.

The shifting paths of the two companies reflect a broader

divergence between Germany and Italy -- original euro members and

the bloc's biggest and third-biggest economies -- since the turn of

the century.

Germany's economy has grown 31% since the euro's creation,

Italy's 7%. Residents of Piedmont, the northern Italian region

where Bialetti was founded, were until recently richer than their

German counterparts in North-Rhine Westphalia, where Zwilling is

based. Today, the opposite is true. Household incomes in

North-Rhine Westphalia have risen by 18% since 2007, to EUR25,700

per inhabitant, while in Piedmont incomes have fallen by 5%, to

EUR21,300 per inhabitant, according to the European Union's

statistics agency.

That widening gap is complicating efforts by the European

Central Bank to phase out stimulus policies: The further countries

are from the eurozone average, the less likely that the ECB's

common strategy will suit them. At worst, it threatens the future

of the currency union, once billed as an engine of economic

convergence.

It wasn't supposed to be this way. The creation of the euro in

January 1999 was expected to raise productivity and living

standards in weaker economies like Spain and Italy, as capital and

trade flowed more easily across the region's internal borders.

Economic fluctuations would fade as countries were forced to

adhere to the same budget rules as Germany. Sharing a common

currency meant countries in Southern Europe couldn't devalue

national currencies to gain a competitive edge. They would have to

become more efficient.

In short, the euro was supposed to create smaller versions of

Germany throughout Europe.

Twenty years on, the euro has been a boon to Germany by creating

a big market using a currency weaker than the deutsche mark was,

helping it export to markets like China. Worker productivity has

increased almost 20% over the period, as German companies invested

heavily in training and new technologies.

But the productivity of Italian workers has flatlined, according

to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and

Development, and exports haven't grown at the same pace as

Germany's. Other Southern European nations like Greece and Portugal

have also diverged economically from Germany since 1999, although

not as dramatically as Italy, according to data from the

International Monetary Fund.

All of which means that the central bank has had to use stimulus

efforts to boost economies across Southern Europe.

"It was a mistake to communicate that each member of the

eurozone had a right to a certain GDP per capita," says Jean-Claude

Trichet, former president of the central bank and an architect of

the currency union. "That depends on the progress of

productivity."

Some economists and politicians blame Italy's stagnation on the

euro itself. While it cut borrowing costs for Italian authorities

and businesses, the euro also removed key economic levers from

national hands, including control over the exchange rate, which

made it harder for Italian companies to remain competitive

internationally.

Increasingly, though, economists argue that the fault lies with

Italian companies and institutions, which they say failed to

navigate the rocky transition to a digitized, globalized

economy.

"It was the failure of Italian enterprises to reorganize

themselves so as to capitalize on...new information technologies

that caused Italy to fall behind from the mid-1990s on," says Barry

Eichengreen, professor of economics at the University of

California, Berkeley.

Italy's family-owned companies, with close ties to banks and

politicians, were good at playing economic catch-up after World War

II. But by the 1990s, their approach of importing technologies

wasn't enough to keep up with an environment of rapid innovation

and change, says Mr. Eichengreen.

German businesses fared better in the increasingly competitive

environment, he says, perhaps because the shock of German

reunification in 1990 forced companies to alter inherited business

practices. For instance, they restrained wage growth to increase

their competitiveness internationally.

"I wouldn't put the euro high up on the list of things that have

created the Italian problem," says Mr. Eichengreen. A return to the

lira would help Italian companies to sell products more cheaply in

international markets, but the problem is, the companies aren't

making enough of the technologically advanced products that would

let them keep pace with top international competitors.

The economic picture was very different when Bialetti was

created. The early decades of the 20th century were a thriving time

for cookware companies in the company's home region, 60 miles

northeast of Turin.

In 1933, company founder Alfredo Bialetti invented an octagonal

coffee pot, known as a moka, which whistles on the stove like a

teapot. The product became enormously popular in Italy. Mr.

Bialetti's firm later merged with a family-run maker of aluminum

pans, Rondine, and listed on the Italian stock exchange in

2007.

Since then, though, Bialetti Industrie has racked up more than

EUR40 million in losses.

The company invested in a chain of retail stores in Italy and

nearby countries in recent years, roughly doubling its staff

numbers. But the bet hasn't paid off. The company attributed a EUR5

million net loss in 2017 in part to difficulties at its stores in

France, Spain and Austria, which necessitated "the partial

write-down of investments in the two-year period 2016-2017,"

according to the company's annual report.

To save costs, Bialetti closed a factory in Omegna in 2010,

which had employed about 120 workers, and outsourced production to

Romania. It wasn't the only company to do so. The town once had

five big cookware firms, but only two remain, says Charles Hubert

de Montbel, managing director of one of the survivors,

Lagostina.

"Omegna is clearly in crisis," he says.

A spokeswoman for Bialetti declined to comment on the company's

performance. She said the company would use EUR40 million in funds

from Och-Ziff to support a three-year business plan, with a focus

on its recently created coffee-capsules business.

Zwilling's operation stands in contrast to Bialetti's. For one,

the knife maker has kept key manufacturing processes close to home.

In a factory at the company's headquarters in Solingen, on the

outskirts of the Ruhr industrial district, the company produces

knives for the U.S. market, which can retail for $100 to $500.

Dozens of orange robotic arms dance and stamp, flitting through

intricate steps that turn sheet metal into knives. Two workers on

the factory floor keep an eye out for any malfunction.

Automation and other technology have given the company a boost

and helped it succeed in recent decades, says Zwilling board member

René Schmitz, and the automation hasn't meant big layoffs because

jobs opened up in new fields as the business grew. The company

employs around 30 engineers in Solingen who develop robotized

production cells, new products and new technologies, he says.

Manual workers create handcrafted specialty knives that can sell

for more than EUR1,700 each.

While Bialetti has had problems outside of Italy, Zwilling has

thrived. Almost 90% of Zwilling's revenue is generated overseas.

China is its biggest market, followed by the U.S.

Bialetti has tried to increase sales in China and the U.S. by

signing new commercial partnerships in those markets in 2014. In

2017, its sales outside Europe were only EUR11 million, or 6% of

its total.

The company now plans to focus on its higher-margin coffee

business. Its sales of ground coffee capsules rose by 13% in the

first half of 2018, taking fourth position in Italy in the capsule

segment, a spokeswoman says.

Mr. Fairless is a Wall Street Journal reporter in Germany. Email

him at tom.fairless@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 20, 2019 09:37 ET (14:37 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2019 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

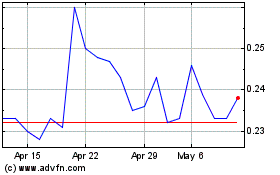

Bialetti Industrie (BIT:BIA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jan 2025 to Feb 2025

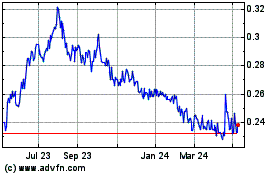

Bialetti Industrie (BIT:BIA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Feb 2024 to Feb 2025