By Julia-Ambra Verlaine

No one said replacing the London interbank offered rate would be

easy, but many regulators and investors contend the cumbersome

process remains on track despite setbacks including the global

coronavirus pandemic.

Deeply rooted in markets after decades and linked to trillions

of dollars of financial products, Libor is slated for replacement

by the end of 2021. Policy makers and regulators moved to scrap the

benchmark after concluding it was balky and prone to manipulation,

as exposed by a 2012 scandal that led to convictions for some

traders and penalties for numerous banks.

If the transition doesn't go as planned, it could leave everyone

worse off. Consumers could end up on the hook for increased

payments on credit-card loans and other borrowings, while small

businesses could face higher fixed rates for loans. About $190

trillion of interest-rate derivatives and $3.4 trillion of business

loans are tied to the rate.

Bankers and others in the market for short-term lending say a

number of developments this year give them confidence that they can

manage Libor's demise and the transition to alternative lending

benchmarks.

A Federal Reserve committee of regulators, banks and asset

managers chose the Secured Overnight Financing Rate, or SOFR, as

the official replacement.

The Alternative Reference Rates Committee, consisting of major

banks, insurers and asset managers alongside the New York Fed, have

been rallying derivatives investors and users of Libor to be ready

for the end. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have said they would stop

accepting adjustable-rate mortgages tied to Libor by the end of

2020. Banks are spending millions of dollars and mobilizing

everyone from lawyers to trading-floor staff.

But efforts were put on ice for more than a month as financial

institutions grappled with tumbling stocks, margin calls and

clients racing for cash as the coronavirus sent markets into a

tailspin prompting unprecedented action by the Fed.

The temporary breakdown of U.S. Treasury markets in March led

some to question the stability of SOFR, which is based on the cost

of transactions in the market for overnight repurchase agreements,

or repos. That is where financial companies borrow cash overnight

using U.S. government debt as collateral.

SOFR dropped to 0.26% on March 16 before doubling the next day,

only to fall again. Moves that week reminded investors of

volatility last September, when SOFR surged above 5% because of

idiosyncratic strains in the repo market.

"There is a growing consensus that SOFR as a replacement for

Libor doesn't really work," said Scott Shay, co-founder of New

York-based Signature Bank.

Smaller and midsize banks are favoring another benchmark:

Ameribor. Established by Richard Sandor, a key player in the

creation of futures markets in the 1970s, Ameribor is based on

rates set on the American Financial Exchange, which he founded.

Smaller banks say Ameribor reflects the cost of funds in trading

in financial markets for banks that aren't among the Fed's

exclusive counterparties -- also known as primary dealers.

Some wonder whether the deadline for the transition away from

Libor will be pushed back. Investment-bank analysts and salespeople

estimate that only a quarter of clients are ready for the benchmark

to disappear.

"I think Libor will go away, but will everybody be ready for it

in 18 months?" said Paul Noring, managing director at BRG, a

consulting firm in Washington, D.C.

Tom Wipf, a vice chairman at Morgan Stanley who is chairman of

the Alternative Reference Rates Committee, said that the move to

SOFR was on track and that the committee was able to double the

number of virtual meetings -- with travel schedules restrained by

lockdowns related to the pandemic -- to get the job done.

He said policy makers weren't pleased with Libor's volatility

during the March stress period, underscoring the need to make the

transition in a timely manner.

"All the concerns that got us here in the first place were

revealed again during that period of market stress," said Mr.

Wipf.

The U.K. regulator in charge of overseeing Libor made it clear a

deadline extension was out of the question. Edwin Schooling Latter,

a senior regulator at the Financial Conduct Authority, said in July

that Libor's death notice wouldn't be pushed back by the impact of

the coronavirus.

"The four to six months ahead of us are arguably the most

critical period in the transition away from Libor," Mr. Latter said

in a speech.

Josh Younger, head of interest-rate derivative research at

JPMorgan Chase & Co., said investors and asset managers saw

significant risks of a delay until U.K. officials came up with a

solution in June to overcome one of the biggest hurdles blocking a

smooth transition away from Libor: so-called tough legacy

contracts.

These include floating-rate notes that require bondholders to

agree on a new reference rate, which is a nearly impossible task,

according to lawyers at companies advising banks and clients.

To avoid litigation, the U.K. government said in June it would

amend the rulebook, handing the FCA, the benchmark's overseer, the

power to craft what some call a "zombie-type" Libor that could

exist for certain legacy contracts.

"Dealing with tough legacy contracts potentially accelerates the

time frame over which this transition can happen," Mr. Younger

said.

Write to Julia-Ambra Verlaine at Julia.Verlaine@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 14, 2020 08:03 ET (12:03 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

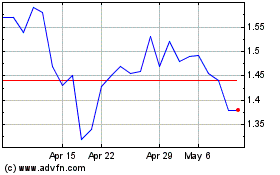

Fannie Mae (QB) (USOTC:FNMA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2025 to Apr 2025

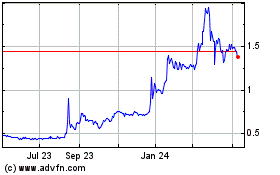

Fannie Mae (QB) (USOTC:FNMA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2024 to Apr 2025