By Alexander Osipovich

Negative oil prices threaten to tarnish the image of West Texas

Intermediate, the U.S. crude benchmark, and hurt the company that

has long relied on it as a key source of revenue: exchange giant

CME Group Inc.

Chicago-based CME is home to the WTI futures contract, which is

a popular way for oil drillers to protect themselves against price

drops or for hedge funds to speculate on the direction of energy

markets.

Futures are contracts that let traders bet on the future price

of commodities like oil and gold, or on financial indexes like the

S&P 500. Unlike stocks, futures can sometimes drop below zero,

particularly in physical commodity markets when storage facilities

fill up and producers pay to get rid of their excess

inventories.

Negative prices have occurred in futures on natural gas,

electricity and some obscure regional grades of crude oil, but

until this week they had never happened in a flagship oil contract

like WTI. On Monday, WTI futures for May delivery slid to minus

$37.63. They later rebounded to $10.01 Tuesday when the May

contract expired.

CME had just changed its computer systems earlier this month to

allow negative pricing in WTI, anticipating such a scenario, and

many traders had discussed it as a possibility. But for many casual

investors, the move was puzzling and appeared to be the latest sign

of market mayhem unleashed by Covid-19.

CME Chairman and Chief Executive Terrence Duffy said in an

interview that WTI futures worked as designed, and their foray into

negative territory was a signal of real market forces at work.

"It's not a price that makes you feel good," he said. "But the

reality is, there is oversupply, there is under-demand that's

virus-driven, and there is nowhere to put the stuff."

While CME doesn't specify how much money it makes from

individual contracts, UBS analysts estimate that about 14% of its

revenue this year will come from energy, which includes oil,

natural gas and other contracts. Last year CME posted $4.9 billion

in total revenue.

CME's WTI franchise could also be hurt if investors sour on

oil-focused exchange-traded funds. This week's price plunge caused

hefty losses for investors in ETFs like the United States Oil Fund,

a popular vehicle for betting on oil prices. Known by its ticker

USO, the fund holds WTI futures and sometimes accounts for a

significant chunk of activity in the contract, lifting CME's fee

revenue.

Last week, USO held more than a quarter of outstanding contracts

for June WTI futures, following massive inflows from investors.

USO's operator, United States Commodity Funds LLC, said Tuesday

that it issued all its registered shares, an unusual event that

effectively turns USO into a closed-end fund and could lead to

further deviations between USO and oil prices.

If WTI futures turn negative again, such deviations could

continue, for the simple reason that an ETF--as a security--can't

trade at prices below zero.

"If the ETF is tied to the futures and the futures go negative

while the ETF can't, there will be dislocations," Mr. Duffy said.

"People should know that before they invest in these

instruments."

Speaking Tuesday afternoon, Mr. Duffy said the WTI expiration

had gone smoothly and CME didn't anticipate any defaults by its

clearing firms, the futures brokerages that act as intermediaries

between traders and the exchange.

Still, it is possible those brokerages' clients, such as

oil-trading firms, suffered big losses. In futures markets, when

contracts are settled, the exchange and its clearing firms move

money from traders with losing bets to traders with winning bets.

If a losing trader can't pay up, the trader's clearing firm must

eat the loss. In extreme cases, client losses can push a clearing

firm into default, which can force other clearing firms to cover

its losses.

That doesn't appear to have happened in the oil market this

week. Still, some fallout from the wild price moves emerged Tuesday

as Interactive Brokers Group Inc., an online brokerage popular with

day traders, reported a provisionary loss of $88 million due to

several clients that blew up because of Monday's collapse in WTI

prices.

After WTI's foray into negative territory, some analysts

suggested trading volumes could migrate from WTI to its main

competitor: the Brent futures contract listed on CME's archrival,

Atlanta-based Intercontinental Exchange Inc., or ICE for short.

"While both products will likely see ramped up volumes because

of crude oil's volatility, we believe Brent, because of its

stability, could gain traction as a stronger benchmark," Piper

Sandler analysts wrote in a Tuesday research note.

CME and ICE have long bickered over which is the better

barometer of the energy market. At stake in the fight are millions

of contracts that change hands each day and the fee revenue that

brings to both exchange operators. Much of that trading is by

investors who want energy in their portfolios and are indifferent

to the arcane details of the WTI and Brent contracts, including

individuals who invest in ETFs linked to oil prices.

WTI futures are tied to the price of oil delivered each month to

the storage hub of Cushing, Okla. Meanwhile, Brent futures track

the price of seaborne crude, relying on an index calculated by ICE.

Even though the two benchmarks have their respective home turf--WTI

is U.S.-focused while Brent is more relevant elsewhere--they tend

to move in tandem.

CME has long argued that WTI is the better benchmark because of

its tighter link to the physical oil market. But its link to the

world of drillers, refiners and shippers of physical crude oil was

also behind this week's plunge into negative prices.

"What's usually the virtue of the WTI contract, its physical

settlement, has actually turned out to be a drawback," said Craig

Pirrong, a finance professor at the University of Houston. "It

demonstrated that there are circumstances when physical settlement

doesn't work well. Granted, these are exceptional

circumstances."

Against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, which has

sharply reduced energy demand, excess oil supplies flooding into

Cushing led storage there to fill up this month. The approaching

expiration of the May WTI futures forced buyers of the contracts to

either take delivery of oil or exit their trades by selling.

With storage hard to find, many sold the futures and found few

others willing to buy them, causing Monday's record drop into

subzero prices. ICE's front-month Brent futures also fell sharply

that day, but settled at the more comprehensible price of $25.57 a

barrel.

Write to Alexander Osipovich at

alexander.osipovich@dowjones.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 22, 2020 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2020 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

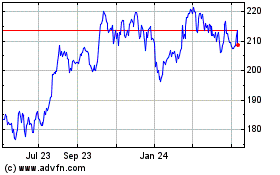

CME (NASDAQ:CME)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jun 2024 to Jul 2024

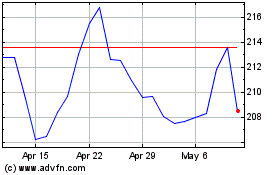

CME (NASDAQ:CME)

Historical Stock Chart

From Jul 2023 to Jul 2024