Graphite and

the US metallurgical Achilles' heel

October 28, 2021 -- InvestorsHub

NewsWire -- via Aheadoftheheard.com -- US recognition of the

importance of critical minerals goes back over 100

years.

In

World War I severe material shortages (tungsten, tin, chromite,

optical grade glass, and manila fiber for ropes) played havoc with

production schedules and caused lengthy delays in implementing

programs. This led to development of the Harbord List – a list of

42 materials deemed critical to the military.

A pre-World War II list of

materials contained a total of 29 materials: 14 were strategic

materials that 'must be based entirely or in substantial part on

sources outside the United States.' There were 15 critical

materials that would be easier to source, perhaps even

domestically, than the strategic materials.

The 1939 Strategic Materials Act

authorized US$100 million to purchase strategic raw materials for a

stockpile of 42 strategic and critical materials needed for wartime

production.

By 1940, small amounts of

chromite, manganese, rubber and tin were procured under the

Strategic Materials Act. The purchases certainly weren't enough and

all throughout the war effort these and numerous other materials

had to be imported in large quantities.

After World War II

the United States created the National Defense Stockpile (NDS) to

acquire and store critical strategic materials for national defense

purposes. The Defense Logistics Agency Strategic Materials (DLA

Strategic Materials) oversees operations of the NDS and their

primary mission is to "protect

the nation against a dangerous and costly dependence upon foreign

sources of supply for critical materials in times of national

emergency."

The NDS was

intended for all essential civilian and military uses in times of

emergencies ie guerrilla warfare in Zaire during the 1970s caused

the worldwide price of cobalt to increase from $6 to $45 a pound,

and a United Nations (UN) trade boycott of Zimbabwe (formerly

Rhodesia) stopped legal exports of chromium from the

country.

By 1948 the WIB's Munitions Board

had developed a list of 51 strategic and critical material groups.

By 1950 the number of required materials had expanded to 54 groups,

representing 75 commodities.

Let's fast forward a few

decades…

A concise summary of US mineral

vulnerabilities was presented to the Industrial Readiness Panel of

the House Armed Services Committee in 1980 by General Alton D.

Slay, Commander, Air Force Systems Command. General Slay pointed

out that technological advances had increased the demand for exotic

minerals at the same time as legislative and regulatory

restrictions had been imposed on the US mining industry.

The 1981 report 'A Congressional

Handbook on U.S. Minerals Dependency/Vulnerability' singled out

eight materials "for which the industrial health and defense of the

United States is most vulnerable to potential supply disruptions" –

chromium, cobalt, manganese, the platinum group of metals,

titanium, bauxite/aluminum, niobium and tantalum – the first five

have been called "the metallurgical Achilles' heel of our

civilization."

In 1981, President Reagan

announced a "major purchase program for the National Defense

Stockpile," saying that it was widely recognized that the nation is

vulnerable to sudden shortages in basic raw materials necessary to

its defense production base.

In 1984 US Marine Corps Major

R.A. Hagerman wrote: "Since World War ll, the

United States has become increasingly dependent on foreign sources

for almost all non-fuel minerals. The availability of these

minerals has an extremely important impact on American industry

and, in turn, on US defense capabilities. Without just a few critical minerals, such as

cobalt, manganese, chromium and platinum, it would be virtually

impossible to produce many defense products such as jet engine,

missile components, electronic components, iron, steel, etc. This

places the U.S. in a vulnerable position with a direct threat to

our defense production capability if the supply of strategic

minerals is disrupted by foreign powers."

In 1985, the secretary of the

United States Army testified before Congress that America was more

than 50% dependent on foreign sources for 23 of 40 critical

materials essential to US national security.

The

1988 article "United States Dependence On Imports Of Four Strategic

And Critical Minerals: Implications And Policy

Alternatives" by G.

Kevin Jones was written in regards to what he thought are the most

critical minerals upon which the United States is dependent for

foreign sources of supply – chromium, cobalt, manganese and the

platinum group metals (PGE).

The

May 1989 report "U.S. Strategic and Critical Materials Imports:

Dependency and Vulnerability. The Latin American Alternative,"

deals with over 90 materials identified in the Defense Material

inventories as of September 1987. At least 15 of these minerals are

considered "key minerals" because the US is over 50% import

reliant.

"The United States has consistently maintained that a strong

domestic minerals and metals industry is an essential contributor

to the nation's economic and security interests…The United States

has a fundamental interest in maintaining a competitive minerals

and metals sector that will continue to contribute significantly to

the nation's economic strength and military security. The industry

represents an $87 billion enterprise that employs over 500,000 U.S.

workers and provides the material foundation for U.S.

manufacturing." The

1980 National Academy of Sciences executive summary of

"Competitiveness of the U.S. Minerals and Metals

Industry"

Despite all of

this, in 1992 Congress directed that the bulk of the strategic and

critical materials the US had accumulated in the National Defense

Stockpile be sold.

The primary purpose of the

National Defense Stockpile was to decrease the risk of dependence

on foreign or single suppliers of strategic and critical materials

used in defense, essential civilian, and essential industrial

applications. The NDS Program allowed for decreasing risk by

maintaining a domestically held inventory of necessary

materials.

While

much of the rest of the world was scrambling to tie up control of

strategic minerals America deliberately hamstrung

itself.

Danger Will

Rogers Danger

"Continued

growth in consumption resources is being driven by growth in China

and the rest of Asia. Chinese companies are increasingly acquiring

assets, as are Indian companies, prompting other global miners into

a race to secure mineral assets of their own." George Fang, Standard

Bank's Head of Mining and Metals China

In his 1989 book

"The Rise and Fall of Great Powers" historian Paul Kennedy argues

that a country with a growing economy prefers to become wealthy

instead of funneling its economic output into the military. While

China's, and other developing countries military might has grown

there is no doubt their greatest concern is to secure the needed

energy and raw commodities necessary to continue their economic

expansion.

The global mining

industry is facing stiff new competition in getting deals done. The

new competitor's for the world's resources have a mandate to secure

long term resource deals for domestic use and have the financing

capabilities any major mining company, or for that matter any

government, would be envious of.

China's state

owned enterprises (SOE) and sovereign wealth funds (SWF) were armed

with hundreds of billions of US dollars from the country's foreign

reserves and sent out to scour the globe for resources – they went

on the hunt to fuel China's exploding economy:

-

SOE/SWFs have no problem dealing in

straight cash and operating in what some might consider high risk

areas

-

The Chinese have a longer term

horizon for their ultimate payoff because they are mostly after off-take

supply agreements from early stage development projects

-

The Chinese

government funds infrastructure projects that

secure the cooperation of the host country with regard to mine

development and off-take agreements

-

Thanks to the

trillions of foreign exchange reserves it currently holds

China offers loans at highly competitive interest rates. For example,

the Export-Import Bank of China (Exim Bank) gave the Angolan

government three loans at interest rates ranging from LIBOR (London

Interbank Offered Rate – the rate banks charge each other on loans)

plus 1.25 percent, up to LIBOR plus 1.75 percent, as well Exim Bank

offered generous grace periods and long repayment terms

The future

production from the deposits that the Chinese, Indians and others

have acquired and developed through state-owned entities flows

directly back to their respective countries bypassing the global

commodity markets.

Critical to the economic and national security of the United

States

Things began to change under

former President Trump, it had to - the US is 100% reliant on imports of 13 critical

minerals.

In 2017 former President Trump

signed an executive order to encourage the exploration and

development of new US sources of these metals.

In December 2017, the U.S.

Geological Survey released its Professional

Paper 1802 titled "Critical Mineral Resources of the United States—

Economic and Environmental Geology and Prospects for Future

Supply".

A critical mineral is defined as

a mineral:

-

Identified to be a nonfuel

mineral or mineral material essential to the economic and national

security of the United States

-

From a supply chain that is

vulnerable to disruption

-

That serves an essential function

in the manufacturing of a product, the absence of which would have

substantial consequences for the U.S. economy or national

security

The report represented the U.S.

Government's most comprehensive assessment of the nation's mineral

resource profile and potential, serving to inform federal mineral

policy.

The report lists 23 metals and

minerals that are critical to "the national economy and national

security of the United States."

In 2018, the US

Government's Critical Minerals List was published.

"The

United States is heavily reliant on imports of certain mineral

commodities that are vital to the Nation's security and economic

prosperity. This dependency of the United States on foreign sources

creates a strategic vulnerability for both its economy and military

to adverse foreign government action, natural disaster, and other

events that can disrupt supply of these key minerals."

On February 24, 2021, President

Joe Biden signed an executive

order (EO) aimed at

strengthening critical U.S. supply chains. Graphite was identified

as one of four minerals considered essential to the nation's

"national security, foreign policy and economy."

"The

United States needs resilient, diverse, and secure supply chains to

ensure our economic prosperity and national security. Pandemics and

other biological threats, cyber-attacks, climate shocks and extreme

weather events, terrorist attacks, geopolitical and economic

competition, and other conditions can reduce critical manufacturing

capacity and the availability and integrity of critical goods,

products, and services."

The EO identifies three

technology sectors as critical supply chains:

-

Advanced

semiconductors

-

High-capacity batteries,

including Electric Vehicle (EV) batteries

-

Pharmaceuticals

The EO also identifies "critical

minerals and other… strategic materials" as a fourth supply chain,

essential to technology manufacturing and the Defense Industrial

Base.

Graphite is a critical mineral

and an essential material for both the renewable and EV Battery

sectors, and for advanced semiconductor

manufacturing.

Graphite is:

-

One of 14 Listed

Minerals for which the U.S. is 100% import-dependent

-

One of 9 Listed

Minerals meeting all 6 of the industrial/defense sector indicators

identified by the U.S. Government report

-

One of 4 Listed

Minerals for which the U.S. is 100% import-dependent while meeting

all 6 industrial/defense sector indicators

-

One of 3 Listed

minerals which meet all industrial/defense sector indicators – and

for which China is the leading global producer and leading U.S.

supplier

The U.S Government's Draft

Critical Minerals List report on graphite stated that

"China is by far

the largest producer of natural graphite, accounting for roughly

two-thirds of world production. Only 4 percent of the world's

natural graphite comes from North America, with no U.S. production

in decades. Although natural graphite was not produced in the

United States in 2016, about 98 U.S. firms, primarily in the

Northeastern and Great Lakes regions, consumed graphite in various

forms from imported sources for use in brake linings, foundry

operations, lubricants, refractory applications, and

steelmaking. Graphite's use in

rechargeable batteries, as well as technologies under development

(such as large-scale fuel-cell applications), could consume as much

graphite as all other uses combined."

There is no substitute for

graphite in an EV battery and lithium-ion batteries are expected to

be the technology that runs electric vehicles for the foreseeable

future, making graphite indispensable to the global shift towards

clean energy.

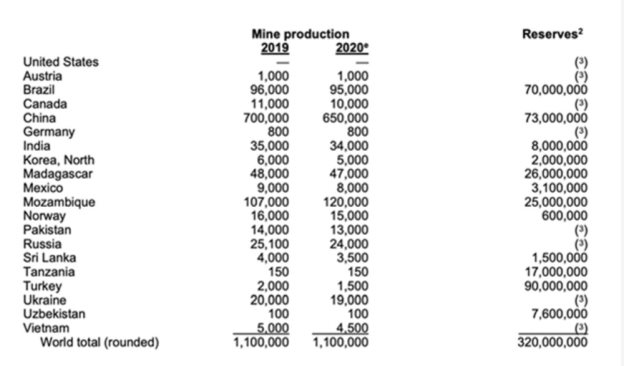

The mineral is sourced from only

a few places. China currently is the world's biggest producer, with

650,000 tonnes of mined graphite in 2020, representing nearly 70%

of global supply.

After China, the next leading

graphite producers are Mozambique, Brazil, Madagascar, Canada and

India. The United States does not produce any natural graphite and

therefore must rely solely on imports to satisfy domestic

demand.

2020 mined

graphite production. Source: USGS

The level of foreign dependence

has increased over the years. The US imported 38,900 tonnes of

graphite in 2016 and 70,700t in 2018.

According to the USGS, in 2020

the US imported 42,000 tons, of which 71% was high-purity flake

graphite, 28% was amorphous, and 1% was lump and chip graphite. The

top importers were China (33%), Mexico (23%), Canada (17%) and

India (9%). But remember, the US is not 33% dependent on China for

its battery-grade graphite, but 100%, since China controls all

spherical graphite processing.

It's thought that the increased

use of lithium-ion batteries could gobble up well over 1.6 million

tonnes of flake graphite per year (out of a total 2020 market, all

uses, of 1.1Mt) — only flake graphite, upgraded to 99.9% purity,

and synthetic graphite (made from petroleum coke, a very expensive

process) can be used in lithium-ion batteries.

The USGS believes that

large-scale fuel cell applications are being developed that could

consume as much graphite as all other uses combined.

Can the mining industry crank out

more graphite every year to match this demand? Color me skeptical.

Between 2018 and 2019, world mine production actually declined by

20,000 tonnes, or 1.8%. Global production in 2019 and 2020 was

exactly the same, 1.1 million tonnes.

Currently there are no producing

graphite mines in the United States, and only 10,000 tonnes a year

is being mined from two facilities in Canada. The fact is, for the

United States to develop a "mine to battery" supply chain at home,

it currently has no choice but to import its raw materials from

foreign countries.

For battery-grade graphite, that

means China, which is growing increasingly adversarial, in terms of

trade, foreign policy and militarily.

Even if the US wants to keep

importing its graphite, doubts have been raised over whether China

could keep up with surging global demand. The top producer has

already taken steps to retain its graphite resources by restricting

its export quota and imposed a 20% export duty.

In short, the days of affordable,

abundant graphite from China are numbered, adding further urgency

for the US to develop its own supply.

The demand for graphite is only

headed in one direction. A White House report on critical supply

chains showed that graphite demand for clean energy applications

will require 25 times more graphite by 2040 than was produced

worldwide in 2020.

We have clearly reached a point

when much more graphite needs to be discovered and

mined.

Graphite

One

Earlier this year, the Federal

Permitting Improvement Steering Committee (FPISC) granted

High-Priority Infrastructure Project (HPIP) status

to Graphite

One Inc. (TSXV:GPH,

OTCQX:GPHOF), which is aiming to develop America's first

high-grade producer of coated spherical graphite (CSG) integrated

with a domestic graphite resource at Graphite Creek,

Alaska.

The HPIP designation allows

Graphite One to list on the US government's Federal Permitting

Dashboard, which ensures that the various federal permitting

agencies coordinate their reviews of projects as a means of

streamlining the approval process.

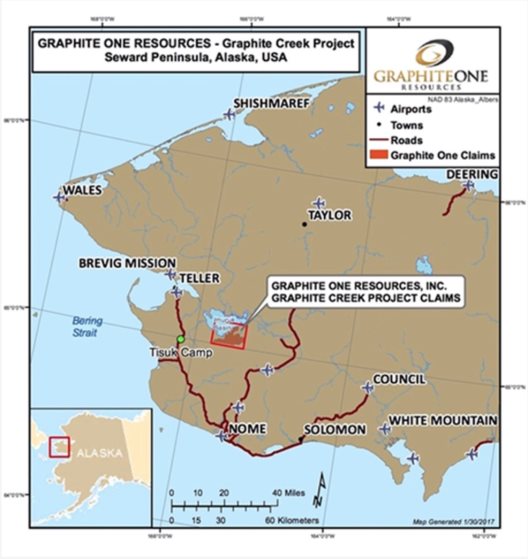

Graphite Creek is the

highest-grade and largest known flake graphite deposit in the US,

spanning 18 km.

The Graphite

Creek property is located 55 km north of Nome, Alaska.

The project is envisioned as a

vertically integrated enterprise to mine, process and manufacture

Coated Spherical Graphite ("CSG") for the lithium-ion electric

vehicle battery market. Graphite One aims to become the first US

vertically integrated domestic producer to serve the US EV battery

market.

The latest resource estimate

(March 2019) for Graphite Creek showed 10.95 million tonnes of

measured and indicated resources at a graphite grade of 7.8% Cg,

for some 850,000 tonnes of contained graphite. Another 91.9 million

tonnes were tagged as inferred resources, with an average grade of

8.0% Cg containing 7.3 million tonnes.

A preliminary

economic assessment (PEA) for the project envisions a 40-year

operation with a mineral processing plant capable of producing

60,000 tonnes of graphite concentrate (at 95% purity) per

year.

"With the recent $21-million in

funding, our efforts have progressed towards completion of the PFS

for the largest known and highest-grade graphite deposit in the

United States. The 2021 field program also initiated the drilling

and additional data collection needed to begin work on the FS after

the PFS is completed. We are very pleased with the successful

execution of the 2021 field program as historical drilling, coupled

with the new data, clearly demonstrates the predictability and

consistency of high-grade, near-surface graphite. With the concepts

and conclusions outlined in the PEA suggesting a 40-year mine life,

the Graphite Creek deposit continues to show potential to be an

essential long-life component of the graphite supply chain, one of

four critical minerals that are on the U.S. National Defense

stockpile list. While the PEA demonstrated the project's economic

viability, we expect these further studies with their optimized

plans for the mine and processing facilities to support improved

economics." Anthony Huston, chief executive officer of Graphite

One.

Once in full production, Graphite

One's proposed graphite products manufacturing plant — the second

link in its proposed supply chain strategy — is expected to turn

graphite concentrates into 41,850 tonnes of battery-grade coated

spherical graphite and 13,500 tonnes of graphite powders per

year.

Material produced from Graphite

Creek would be almost sufficient to supply the entire nation's

graphite demand given current import totals.

But these production figures were

based on resource estimates prior to the 2019 update, leaving room

for potentially higher production.

Conclusion

Many do not realize do not

realize that without graphite, lithium-ion batteries cannot be

made. There is no substitution for graphite in a lithium battery

anode, making graphite as crucial to the green-energy transition as

lithium itself.

That fact should sound the alarm

for those following graphite demand and supply.

For many years the United States

didn't mind being dependent on out-of-country suppliers for

critical minerals like graphite. It was convenient. But today

convenience is being replaced with understanding the role of

critical minerals in a nation's economic health and military

strength.

Critical minerals are finally

getting the attention they deserve.

Graphite One is a company on the

move with the largest and highest-grade flake graphite deposit in

the United States.

What GPH has discovered so far

though is only a small portion of the geological trend under

consideration. I believe Graphite Creek will become a mine and that its production will

supply a large percentage of US domestic graphite demand. I

therefore see GPH as an important link in America's burgeoning

"mine to battery" supply chain which is why I own

shares.

Graphite One

Inc.

TSXV:GPH,

OTCQX:GPHOF

Cdn$1.56, 2021.10.26

Shares Outstanding

81.5m

Market cap Cdn$129.9m

GPH website

Richard (Rick)

Mills

aheadoftheherd.com

subscribe

to my free newsletter

Legal Notice

/ Disclaimer

Ahead of the Herd

newsletter, aheadoftheherd.com, hereafter known as AOTH.

Please read the

entire Disclaimer carefully before you use this website or read the

newsletter. If you do not agree to all the AOTH/Richard Mills

Disclaimer, do not access/read this website/newsletter/article, or

any of its pages. By reading/using this AOTH/Richard Mills

website/newsletter/article, and whether you actually read this

Disclaimer, you are deemed to have accepted it.

Any AOTH/Richard

Mills document is not, and should not be, construed as an offer to

sell or the solicitation of an offer to purchase or subscribe for

any investment.

AOTH/Richard Mills

has based this document on information obtained from sources he

believes to be reliable, but which has not been independently

verified.

AOTH/Richard Mills

makes no guarantee, representation or warranty and accepts no

responsibility or liability as to its accuracy or

completeness.

Expressions of

opinion are those of AOTH/Richard Mills only and are subject to

change without notice.

AOTH/Richard Mills

assumes no warranty, liability or guarantee for the current

relevance, correctness or completeness of any information provided

within this Report and will not be held liable for the consequence

of reliance upon any opinion or statement contained herein or any

omission.

Furthermore,

AOTH/Richard Mills assumes no liability for any direct or indirect

loss or damage for lost profit, which you may incur as a result of

the use and existence of the information provided within this

AOTH/Richard Mills Report.

You agree that by

reading AOTH/Richard Mills articles, you are acting at your OWN

RISK. In no event should AOTH/Richard Mills liable for any direct

or indirect trading losses caused by any information contained in

AOTH/Richard Mills articles. Information in AOTH/Richard Mills

articles is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to

buy any security. AOTH/Richard Mills is not suggesting the

transacting of any financial instruments.

Our publications

are not a recommendation to buy or sell a security – no information

posted on this site is to be considered investment advice or a

recommendation to do anything involving finance or money aside from

performing your own due diligence and consulting with your personal

registered broker/financial advisor.

AOTH/Richard Mills

recommends that before investing in any securities, you consult

with a professional financial planner or advisor, and that you

should conduct a complete and independent investigation before

investing in any security after prudent consideration of all

pertinent risks.

Ahead of the Herd

is not a registered broker, dealer, analyst, or advisor. We hold no

investment licenses and may not sell, offer to sell, or offer to

buy any security.

Richard owns shares of

Graphite One

Inc. (TSXV:GPH).

GPH is a paid advertiser on his site aheadoftheherd.com

SOURCE: aheadoftheheard.com